Can we please prioritize switching to the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) to measure protein quality and then communicate that info to consumers when we share with them the vital role of ruminant animals to soil health?

Yes, that’s a mouthful, but it needed to be said. Climate change, soil health, feeding the growing population…it seems that so many are working on these issues, but not bringing them full circle. Hold onto to your seats while you read how switching to DIAAS to measure protein quality will be a win-win for the dairy industry.

Here we go. The fact is we need ruminant animals, such as cows, for healthy soil and to convert plants that humans cannot eat into highly nutritious foods that we can. Think milk and steak.

The fact is that two-thirds of global agriculture land is not suitable for growing crops that humans can digest for energy and nutrition. But these lands are suitable for growing grasses and similar plants that ruminant animals consume. These plants are basically sources of cellulose. In fact, half of all organic carbon on earth is tied up in cellulose. Humans are not able to use this carbon for energy. Ruminants can, and they do so very efficiently.

Ruminants digest cellulose and convert it into foods that humans can eat. They make all of that organic carbon that cannot be digested by humans available to humans in the form of high-quality protein, essential fatty acids such as omega-3s and conjugated linoleic acid, and an array of other nutrients. Milk, for example, provides calcium, potassium, phosphorus, protein, vitamins A, B2, B3 and B12.

Think about a stalk of corn, which provides two to three cobs. Humans can only digest the kernels, and for that matter, not even all of the kernel. The fibrous outer shells of corn kernels pass through the gastrointestinal system undigested due to lack of the necessary digestive enzyme. The rest of that corn plant is useless to humans for energy; however, it’s a meal for ruminant animals such as cows. Cows effectively convert the nutrients in that stalk, husk and cob to meat and milk for human consumption.

This is why we need ruminant animals to feed the projected 9.7 billion humans who will inhabit earth in 2050.

Ruminant animals also provide manure to fertilize crops and help build healthy soil for crops to grow. While ruminants are a source of greenhouse gas (GHG), the industry is doing so much in this space that many are confident that with appropriate regenerative crop and grazing management, ruminants will not only reduce overall GHG emissions, but also facilitate provision of essential ecosystem services, increase soil carbon sequestration and reduce environmental damage. That’s another mouthful.

And then, after all that, ruminant animals feed us the highest-quality protein available. Yet, current U.S. regulations prevent marketers from communicating this information.

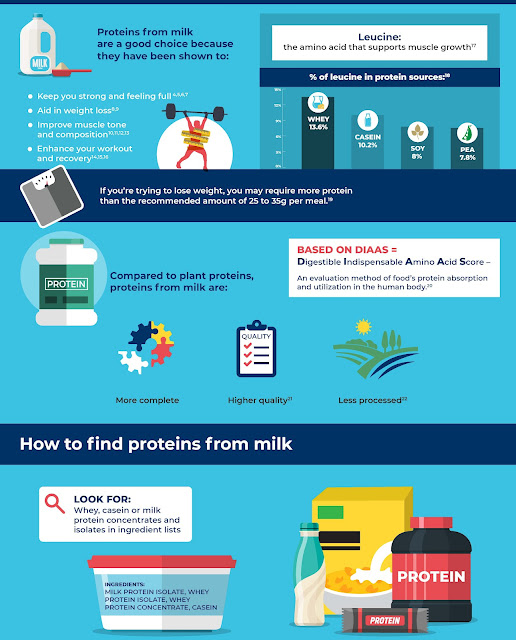

It’s been almost 10 years since a report from the Expert Consultation of the Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations (FAO) recommended a new, advanced method for assessing the quality of dietary proteins. It’s the DIAAS. This analysis enables the differentiation of protein sources by their ability to supply amino acids for use by the human body. The new method demonstrates the higher bioavailability of dairy proteins when compared to plant-based protein sources.

Data in the FAO report showed whole milk powder to have a DIAAS score of 1.22, far superior to the DIAAS score of 0.64 for peas and 0.40 for wheat. When compared to the highest refined soy isolate, dairy protein DIAAS scores were 10% to 30% higher.

Dairy proteins have an exceptionally high DIAAS score because of the presence of branched-chain amino acids, which help stimulate muscle protein synthesis. Each dairy protein has more branched-chain amino acids than egg, meat, soy and wheat proteins. Whey protein, specifically, is seen as higher quality because of the presence of leucine, a branched-chain amino acid accountable for muscle synthesis.

Currently the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score is used to assess of protein quality. This does not demonstrate dairy protein’s superiority. This information is very important for feeding that growing population. The answer is not plants, or at least not plants alone.

“As headlines proliferate around the need to supply protein to an ever-growing global population, the common argument has emerged that people around the world are already consuming more than they need,” according to Paul Moughan, distinguished professor at Massey University and Riddet Institute Fellow Laureate. “While this may indeed be true in terms of total protein, it is unfortunately not the case when it comes to their intake of available protein. For example, a child in India consuming a diet that is heavily based on cereals and root crops, may be getting plenty of protein containing foods, but they could still be heavily deficient in available protein and key amino acids. This deficiency can lead to stunted growth during childhood and result in them never fulfilling their true potential.”

Riddet Institute led a research program known as Proteos that is addressing the supply of protein for human diets. Proteos is funded by a consortium of commercial food organizations through the Global Dairy Platform.

The first stage of Proteos has been completed. This was a collaboration between the Riddet Institute in New Zealand, Wageningen University in The Netherlands, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and AgroParisTech in France. The researchers developed, standardized and validated methods based on the growing population to determine the digestibility of amino acids for human foods. The methods were applied in different laboratories in different parts of the world and achieved consistent results, according to Dr. Moughan.

They are now working with Wageningen University and the University of Illinois to examine the digestibility of numerous protein sources in a form as consumed by humans using DIAAS. An openly available global database of protein quality will be constructed, including 100 different protein sources. These protein sources will be from a large range of different protein types, including protein sources commonly consumed in developing countries.

Dairy proteins are expected to lead the list.

Now, let’s back track just a minute to address the GHG emissions issue with ruminant animals. There’s a lot going on in this space, and imagine if everything came together at the same time…and sooner than later.

In 2008, U.S. dairy was the first in the food agricultural sector to conduct a full-life cycle assessment at a national level. The Fluid Milk Carbon Footprint Study was published in 2010 and showed that U.S. dairy contributes 2% of all U.S. GHG emissions. As of 2007, producing a gallon of milk uses 90% less land and 65% less water, with a 63% smaller carbon footprint than in 1944. Thanks to increasingly modern and innovative dairy farming practices, the environmental impact of producing a gallon of milk in 2017 shrunk significantly, requiring 30% less water, 21% less land and a 19% smaller carbon footprint than it did in 2007. That’s the same as the amount of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere by half a million acres of U.S. forest.

At Transform Food USA 2022/Transform Supply Chains USA 2022, a conference organized by Reuters Events and held Nov. 1-2 in Chicago, I met with Dr. Greg Thoma, associate professor with Colorado State University’s AgNext program. He is the author of the Fluid Milk Carbon Footprint Study. (At the time of the study, Dr. Thoma, a chemical engineer, was with University of Arkansas’ Applied Sustainability Center.)

Highlights from the Transform meeting can be found in an article titled “Prioritizing production key to creating sustainable solutions,” which I wrote for Food Business News. Link

HERE.

There was a great deal of conversation at the Transform meeting regarding soil health and the need to put the farmer first. There’s was discussion on improving the breeding of food crops, e.g., soybeans with higher protein content, as well as indoor farming and regenerative agriculture practices.

Dr. Thoma explained that the carbon footprint study was a significant first step in the dairy industry’s effort to measure and improve its environmental performance. More efforts are underway.

AgNext, for example, recently installed what it calls “climate smart research feeding pens,” which allows for evaluation of dietary and management strategies that impact cattle GHG emissions. The portable feeding stations measure emissions while the animal eats. In the case of AgNext’s cattle, these machines dispense a feed treat (alfalfa pellets) to draw the cattle’s attention. Once drawn to the treat, the animal will eat and stand still for emissions to be measured for three to five minutes. Gasses, including carbon dioxide, methane, hydrogen and oxygen, are measured in real time.

“These feedlot pens allow for data replication to determine scalability of solutions,” said Dr. Thoma.

That scalability will enable farmers to implement regenerative agriculture initiatives and quantify the benefits. This may lead to the production of climate-conscious foods and ingredients. Marketers can share this data with consumers, who then can feel that their purchase is making a difference.

Now, it’s been a little more than a year from when “Pathways to Dairy Net Zero” was launched. This climate initiative demonstrates the global dairy sector’s commitment to reducing GHG emissions while continuing to produce nutritious foods for six billion people and provide for the livelihoods of one billion people.

Initial research found that the dairy sector already has the means to reduce a significant proportion of emissions--up to 40% in some systems--by improving productivity and resource use efficiency. Researchers are identifying plausible GHG mitigation pathways for different dairy systems globally, in particular methane reduction.

In the U.S., the Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy has its Net Zero Initiative, an industry-wide effort that commenced in 2020 and is helping U.S. dairy farms of all sizes and geographies implement new technologies and adopt economically viable practices. The initiative is a critical component of U.S. dairy’s environmental stewardship goals, endorsed by dairy industry leaders and farmers, to achieve carbon neutrality, optimized water usage and improved water quality by 2050.

“The U.S. dairy community has been working together to provide the world with responsibly produced, nutritious dairy foods,” said Mike Haddad, chairman, Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy. “With the entire dairy community at the table--from farmers and cooperatives to processors, household brands and retailers--we’re leveraging U.S. dairy’s innovation, diversity and scale to drive continued environmental progress and create a more sustainable planet for future generations.”

It takes a united team. That’s us!

.png)

.jpg)

.png)